Chapter 9: Information Architecture¶

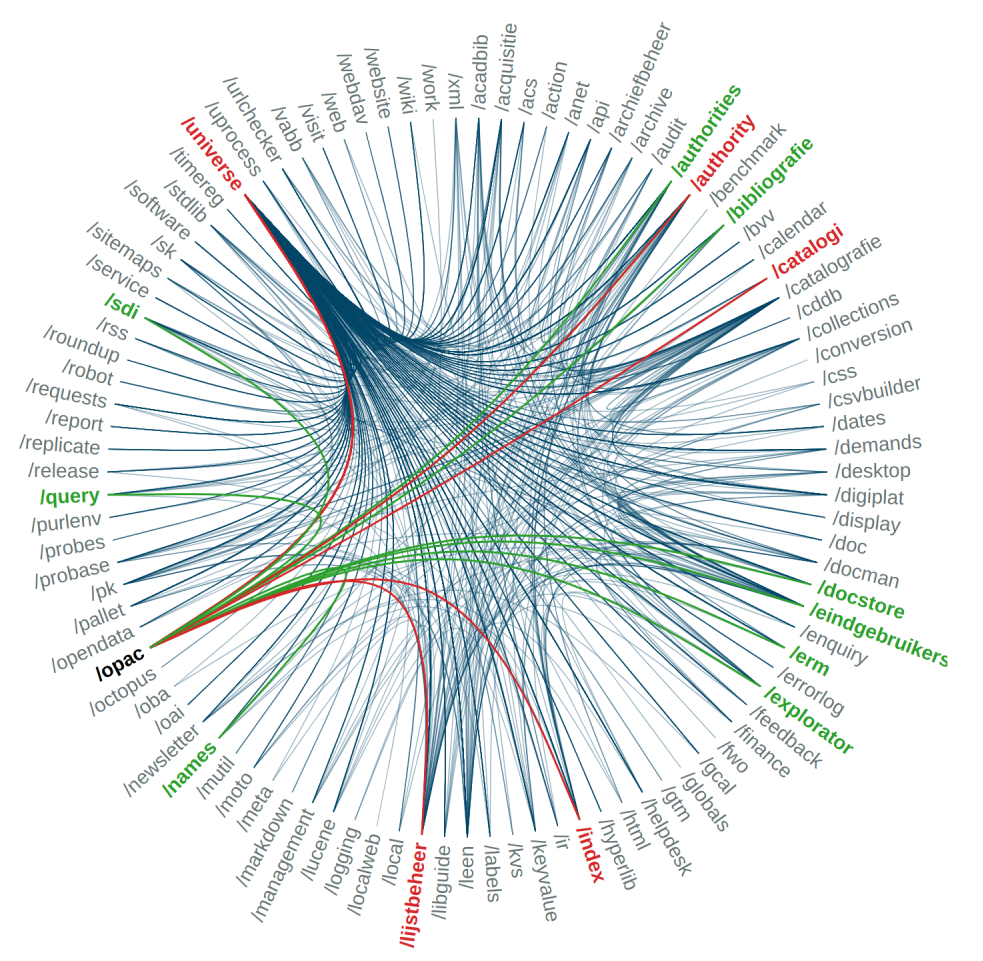

Brocade software visualization

In this chapter about the Brocade library management system (LMS) we will try to tie the previous chapters together. Above all, the aim is the illustrate the overall architecture of an information system, i.e. how different technologies come together to make up a system.

Brocade Library Services¶

(source: Wikipedia)

Brocade, in full “Brocade Library Services” is a web-based library information management system developed by the University of Antwerp (UAntwerp) in 1998 by a section of the University Library called Anet. Brocade is designed as a web-based application, sold via a cloud license model. The system is multilingual and uses open source components.

Brocade offers library and archival institutions a complete suite of applications allowing them to:

create, maintain and publish bibliographical, archival and documentary databases;

automate all back-office tasks in a library (cataloguing, authority control and thesaurus management, patron administration, circulation, ordering, subscription control, electronic resource management, interlibrary lending and document delivery) and an archival institution (ISAAR authorities, archival acquisitions, ISAD descriptions, descriptions of objects such as manuscripts, photos, letters, …)

offer electronic services to the library end-users (online public access catalogue, SMS services, personalized MyLib-environment, document requests, alerting service, self-renewal, …)

The networked topology of the application lets libraries work together, share information, share catalogues, while still keeping their own identity and independency when it comes to typical local functions such as acquisition and circulation.

Brocade is a completely web-based application, available anywhere, anyplace and anytime (where an internet connection is available) using standard browsers such as Firefox, Internet Explorer, Safari, Opera and Chrome. Brocade does not require installation of specific clients on the user’s desktop. Installation of software on local PCs is kept to a strict minimum: a PDF reader and an application called Localweb which caters for ticket printing and provides basic circulation operations when the network fails. As the Brocade server is hosted and managed centrally, software updates and system upgrades do not require interaction from the local library staff. Brocade uses a central software repository from which bug fixes can easily be installed overnight to all Brocade systems. All new releases are also installed centrally from this repository.

Target customers for Brocade are libraries (public libraries, academic and education libraries, special libraries), museums, documentation centres and archival organisations. The Brocade system has been implemented in various libraries in Belgium, The Netherlands and South Africa.

Library workflow¶

To make this concrete, let’s have a look at the typical library workflow and how Brocade automates that. Let’s take a single issue of a scholarly journal as an example:

Brocade allows libraries to manage subscriptions to journals.

These will periodically create an order to be sent out.

When the copy/copies are delivered, they come with an invoice that is registered for follow-up.

Certain publications cause automatic notifications for patrons.

Before circulation, the catalography department registers bibliographic metadata for the publication, including a barcode and shelfmark.

Part of catalography is the authorization of names, places, subjects; to make them more searchable.

Patrons can then search for the publication in the OPAC.

In the OPAC, there are also features to request or reserve a publication.

After that, the publication can be loaned out.

Patrons can check their loans and other personal information, such as fines.

Another possibility is that the publication is requested from an outside library via Interlibrary Loan.

Sometimes it is sent, or a physical copy of it. Other times a digitisation is made, which is uploaded into the system and provided in the OPAC.

(And mind you, this is just library workflow. Brocade also automates archives, musea and documentation centers – all of which have different workflows.)

Preliminary: understanding standard streams¶

Before we can have a look at the architecture of such a complex system, we need to say something about how different computer programs interact through so-called standard streams:

In computer programming, standard streams are interconnected input and output communication channels between a computer program and its environment when it begins execution. The three input/output (I/O) connections are called standard input (stdin), standard output (stdout) and standard error (stderr). Originally I/O happened via a physically connected system console (input via keyboard, output via monitor), but standard streams abstract this. When a command is executed via an interactive shell, the streams are typically connected to the text terminal on which the shell is running, but can be changed with redirection or a pipeline. More generally, a child process inherits the standard streams of its parent process.

Communication through streams makes it possible for different programs, and therefore different technologies, to communicate.

For example, consider the following Python program:

import subprocess

message = input("Message? ")

input_bytes = message.encode()

process = subprocess.run("/home/tdeneire/Dropbox/code/go/test/main",

input=input_bytes, capture_output=True)

result_bytes = process.stdout

result_string = result_bytes.decode()

print(result_string)

When we execute this, the following happens:

a Python process is launched that asks for user input

a Go sub-process is launched

this sub-process receives input from the parent and returns its output to the parent process

the parent process prints the result

package main

import (

"io"

"os"

"strconv"

)

// compiled as /home/tdeneire/Dropbox/code/go/test/main

func main() {

data, err := io.ReadAll(os.Stdin)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

length := strconv.Itoa(len(data))

io.WriteString(os.Stdout, length)

}

The notion of one process’ output being another process’ input is vital for building software systems.

Brocade system architecture¶

Server¶

The story of Brocade starts with a server, a physical machine located in the University of Antwerp’s server farm. It currently runs Red Hat OS and uses Ansible for application deployment and configuration management. This means we do not manually install applications, but automate the installation process and describe it in detail in (.yaml) configuration files. This not only saves our system engineer a lot of time, it also ensures the consistency of the installation process (correct versions of software, dependencies, installation order, …)

The following components are key parts of our server infrastructure:

MUMPS¶

MUMPS (or “M”) is both a key-value database and an integrated programming language (which used to be quite common). How does that work? Well, MUMPS is an interpreted language, so you have an interpreter (same as in Python) at your disposal where you can do things like this:

s ^USERS(1,"first")="Tom"

s ^USERS(1,"last")="Deneire"

s ^USERS(1,"email")="tom.deneire@uantwerpen.be"

This instruction tells the database to define a global variable (the ^ caret sign makes it a global), which will be available both during the program’s runtime and which will be saved to an area of physical disk space designated for these globals, making it effectively a database.

The structure is that of a subscripted array, which is equivalent to this in JSON

{"USERS":

{

"1": {

"email": "tom.deneire@uantwerpen.be",

"first": "Tom",

"last": "Deneire"

}

}

}

Of course, you can also run code from files in MUMPS.

There are now, and have always been, several MUMPS implementations, one of which is G.TM. G.TM is now open source, which allows a company called YottaDB to distribute it and offer database support. For Brocade, YottaDB is our database provider, but technically our MUMPS platform and compiler is G.TM.

YottaDB also provide a C and Go wrapper, so you can access the MUMPS database without using MUMPS, if you want. You see, MUMPS is a language that, like all languages, has its flaws. On the other hand, MUMPS is simple, fast and powerful, and is codified in an ISO-standard which means that is allows for very stable code to build applications that can stand the test of time.

In any case, MUMPS is the heart of Brocade: the database that records all of our data and metadata. For instance, this is how book c:lvd:123456 which we used as an example in chapter 5 is stored in our database, in global ^BCAT:

^BCAT("lvd",123456)="^UA-CST^53320,52220^tdeneire^65512,39826^^^"

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"au",1)="aut^0^oip^Sassen^Ferdinand^^nd"

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"co",1)="190 p.^^^^^oip^nd^normal^^^^^^^"

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"dr","paper")=""

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"ed",1)="oip^2 ed.^nd"

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"im",1)="Antwerpen^0^nd^YYYY^1932^^YYYY^^^pbl^0^Standaard^oip^nd^normal"

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"lg",1)="dut^dt"

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"lm","zebra")=""

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"nr",1)="co^0^1.248929^oip^nd^"

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"nr",2)="oclcwork^0^48674539^oip^^"

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"nr",3)="oclc^0^781576701^oip^nd^"

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"opac","cat.all","*")=""

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"opac","cat.anet","*")=""

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"opac","cat.ua","*")=""

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"pk","TPC")=""

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"pk","TPC","p:lvd:5554031")="^LZ 10/3/12^more-l^^^^^^^^^^^"

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"pk","UA-CST")=""

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"pk","UA-CST","p:lvd:205824")="^MAG-Coll 113.1/2^mag-o^^^^^^^0^^^^"

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"pk","UA-CST","p:lvd:205824","vo","-")=""

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"pk","UA-CST","p:lvd:205824","vo","-","o:lvd:261838")=""

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"pk","UA-CST","p:lvd:205825")="^FILO 19 A-SASS 32^filo-a^^^^^^^^^^^"

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"pk","UA-CST","p:lvd:205825","vo","-")=""

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"pk","UA-CST","p:lvd:205825","vo","-","o:lvd:261839")=""

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"re","lw")="1^1"

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"re","lw"," ","c:work:45740")=""

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"re","vnr")="1^1"

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"re","vnr"," 1932: 4","c:lvd:222144")=""

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"su","a::19:1")=""

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"su","a::93.001:1")=""

^BCAT("lvd",123456,"ti",1)="h^dut^1^0^oip^Geschiedenis van de wijsbegeerte der Grieken en Romeinen^^fp"

Apache, Javascript and PHP¶

Our server uses Apache webserver to host a website with a URL that ends in ?brocade.phtml. This file is where we link up our frontend (HTML/Javascript/CSS) and backend (MUMPS/Python/Go).

The p in brocade.phtml stands for PHP, it is a HTML file which can also execute PHP code. PHP (unlike Javascript) runs server side which means it can access the server’s shell. The shell can then start a MUMPS that processes the input HTML (e.g. username and password), performs a database operation (e.g. lookup access rights in the database) and then produces output HTML over stdout. This is then read by PHP again to enable the server to render it on screen again.

Python¶

Our server also has a Python installation, including several (but well-chosen) third-party packages (such as pylucene, lxml or xlsxwriter). In Brocade, Python is used for many different things, but one of its main purposes is to run what we call toolcat applications.

Toolcat applications are typically pieces of specific backend software that offer support or extensions for other applications.

Some examples include:

mutil: maintenance of MUMPScrunch: storage monitoring (disk space, database regions, …)musqet: export of MUMPS data to.sqlitedocman: file storage, e.g. images, PDFs, …explorator: our Python wrapper (usingpylucene) for Lucene

So if a user uses Brocade to export a dataset in .sqlite, what happens under the hood is that MUMPS goes to the shell to trigger a musqet command. This is then executed with Python and the result is stored on the server with docman. The result is offered to the user as a download link.

Over the years, Anet has also developed Python packages that are able to read data from the MUMPS database or send data to it.

Other software¶

Other software installed on the server, includes Go (for systems programming, e.g. scheduling tasks such as cleaning obsolete files) and Lucene (Java) for indexing.

Example¶

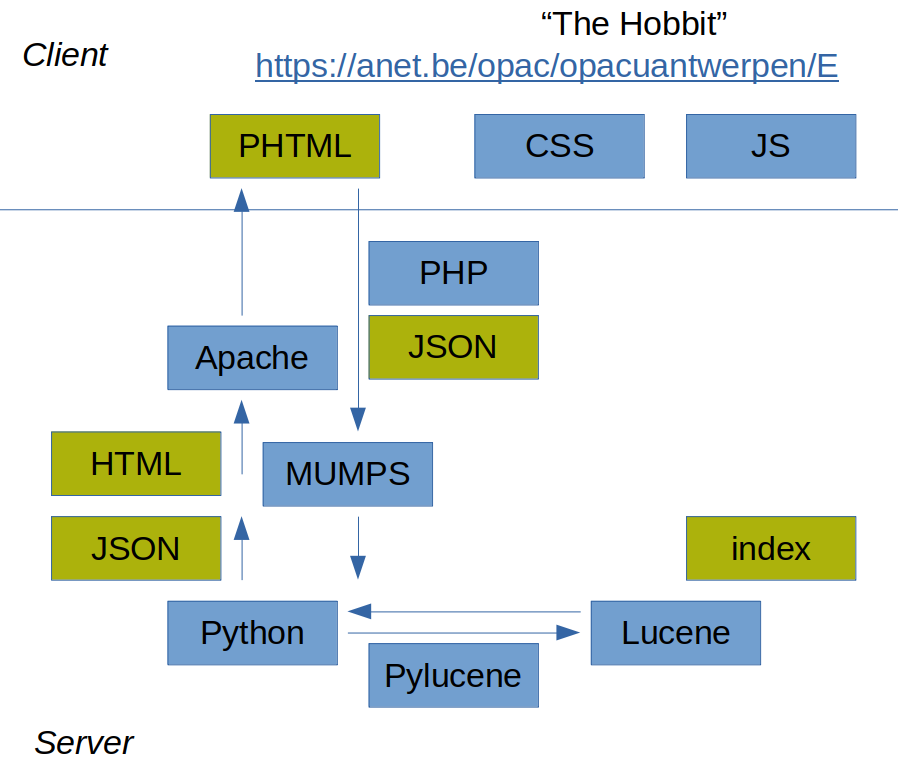

Let’s look at a concrete example to illustrate how the different components of this information architecture work together.

OPAC¶

When a user enters a search term in the OPAC, this happens in a web browser that renders an HTML page, with layout defined in CSS and client-side functionality written in JavaScript. This page is being served by the Apache web server.

PHP¶

This HTML includes a section of PHP (hence the file extension is .pthml), which allows the client to send a command to the backend (server) that includes some data from the web form as JSON, for instance the search string “The Hobbit”.

MUMPS 1¶

This command starts a MUMPS process, which is able to use the JSON web input to figure out what needs to happen.

Python¶

Like PHP, MUMPS can also start another process, for instance, a Python instruction. We use this to access the Lucene index. Via the Pylucene module, the Lucene index is queried for the term “Hobbit” (after tokenisation), which yields a result of a set of LOIs.

MUMPS 2¶

This search result is then passed back to MUMPS, again using JSON. With it, MUMPS is able to populate a new HTML page, which displays a list of found LOIs with some additional information (like author, full title, cover image), that is present in the MUMPS database.

Apache¶

This HTML string is then handed over to Apache, which serves it as a response to the original request (input of search string) performed by the client.

Customization through metadata¶

Since we construct the HTML that Brocade serves to the web client, it is possible to customize that HTML according to our clients’ needs.

Language codes¶

One example of this that all of our software is language independent. Whenever the HTML needs to contain a word like “Title” or “Author”, the Brocade software actually contains a (language code). When the screen HTML is constructed, we translate that code using system settings (language) and a translation table of these language codes, like so:

lgcode Titel:

N: Titel

E: Title

F: Titre

Meta-information¶

Similarly all kinds of other settings can be customized using meta-information. For instance, when registering a book’s title, Brocade libraries can choose to allow different sets of possible “title types” (like main title, subtitle, alternate title, …). Library A can use a different set of choices than library B. The system keeps track of such preferences and, again, when the screen HTML is rendered, only the necessary title types are displayed…

Production server¶

So far we’ve been speaking about ‘the’ server, but there are in fact several.

The one mentioned was actually the development server (we call it “presto”), as of course we don’t code on the production server (“moto”). If you mess that software up, all users are affected. (There are even more servers, e.g. a demonstration server, a storage server and - importantly - a replication server)

This works like this: we are currently developing Brocade version 5.90, whereas on the production server we have Brocade version 5.80 running, which we leave untouched (unless there are bugs).

When we are finished with 5.90 and want to install the new release, we basically copy the new software from the development server to the production server, while leaving the data (e.g. the MUMPS database) intact.

Optional exercise: YDB Acculturation Workshop¶

If you want a taste of what it is like to set up your own information system, you can take a look at the YottaDB Acculturation Workshop which the company has made available. This will guide you through setting up YDB in a virtual container and addressing the MUMPS database, either with MUMPS, C or Go (they are currently working on a Python wrapper).