Chapter 6: Information about Information¶

Credit: Charlie Brown by Charles M. Schulz

TL;DR: Metadata is created data about other data. There can be no proper use of metadata without a good understanding of its structure and the way it was created.

Metadata¶

Earlier on we saw how, from a practical point of view, it makes more sense to talk about data models instead of information models. In this chapter, we are going to do the same with information itself. Indeed, a lot of what happens in information science does not have to do with information per se, but with information about information, also known as metadata:

Wikipedia says:

Metadata is “data that provides information about other data”. In other words, it is “data about data.” Many distinct types of metadata exist, including descriptive metadata, structural metadata, administrative metadata, reference metadata and statistical metadata.

In this discussion, we will focus especially on descriptive metadata, i.e. descriptive information about a resource.

Descriptive metadata is used for discovery and identification. If we think about books, for example, descriptive metadata would include elements such as title, author, date of publication, etcetera.

Another example is Exif (Exchangeable image file format), a metadata standard that specifies the formats for images, sound, and ancillary tags used by digital cameras (including smartphones), scanners and other systems handling image and sound files recorded by digital cameras.

Metadata is important!¶

Metadata might seem trivial – in fact, I don’t like the word ancillary (inspired by Wikipedia) in the previous paragraph – or non-essential. However, metadata performs a huge and crucial role in information science and even software development.

What do we mean with metadata for software? Good software is as generic as possible. This means that applications will strictly separate their business logic (e.g. invoice system) and the metadata the application uses (e.g. database of clients, suppliers, etc.). Without the latter, the former is just an empty shell.

Consider, as an illustration, this story about a bug in the Samsung Blu Ray player, where a faulty XML logging policy file (metadata!) caused boot failure!

It’s complicated¶

The aforementioned definition of metadata as “data about data” somewhat misses the mark. In order to understand the full complications of metadata, we need to take a look at a concrete example.

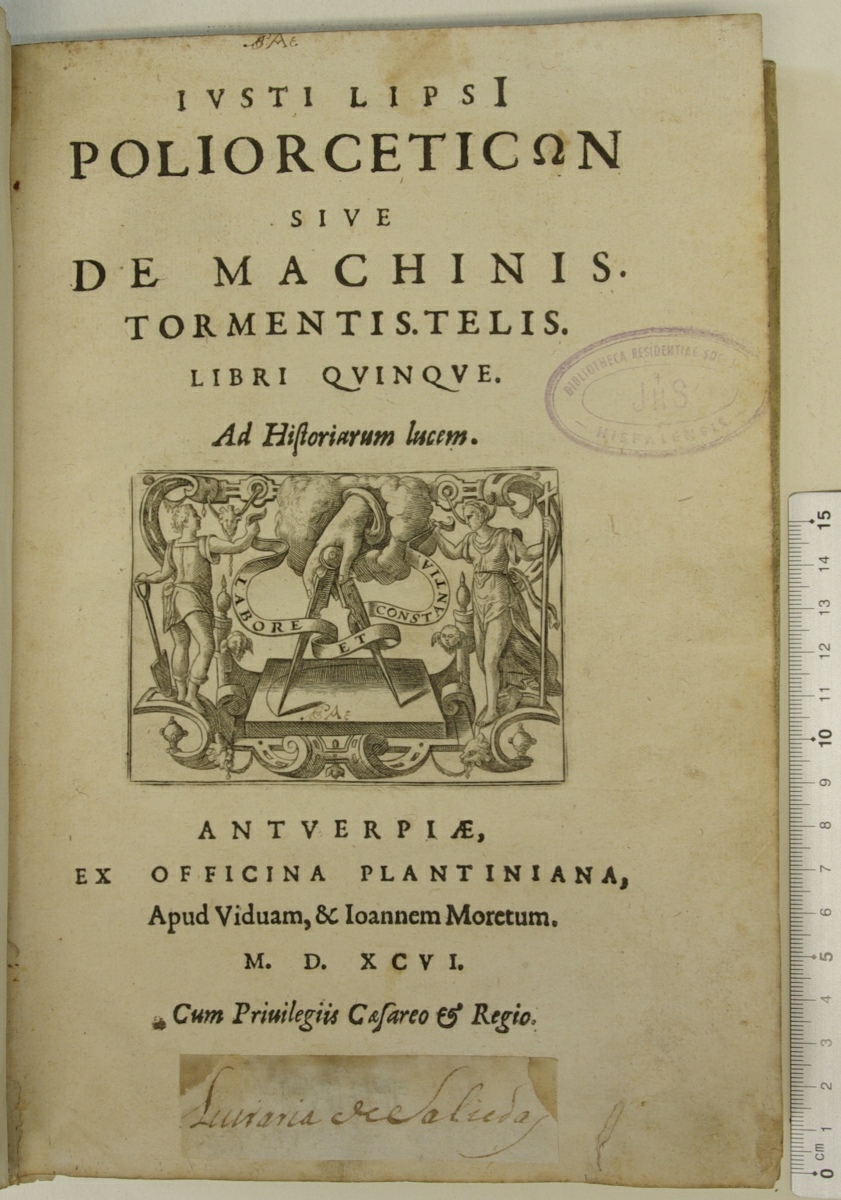

Have a look at the title page of Justus Lipsius’s work Poliorcetica, a treatise on ancient war machinery:

Credit: photo: STCV catalogue, copy: UA-CST MAG-P 13.74 (f. *1 recto)

STCV¶

STCV, the Short-Title Catalogue Flanders, catalogues this book’s title as follows:

Category |

Metadata |

|---|---|

Title |

Title page: Poliorceticωn sive De machinis. Tormentis. Telis. Libri qvinqve |

Author |

Title page: Ivstus Lipsius [Lipsius, Justus] |

. |

External: van Veen, Otto [Illustrator] |

. |

External: van der Borcht, Pieter I [Illustrator] |

Publication |

Title page: ex officina Plantiniana, apud viduam, & Ioannem Moretum [Rivière, Jeanne & Jan I Moretus] |

. |

Title page: Antverpiæ [Antwerp] |

. |

1596 |

Language |

Latin [Target language] |

Now let’s compare this to the title page.

For instance, we see that the difference in case, i.e. lower case, upper case and small caps, has disappeared. This might seem trivial, but did you realise that in Renaissance Latin a capitalized final “I” stands for “ii”? So the full title is actually, “Ivsti Lipsii…” Or, suppose that someone is studying the use of capitalization in title layout as a marketing means. This is vital information that is missing.

Moreover, when we focus on the title words, we see small differences. Whereas the title page does not have a space between “Tormentis.Telis”, the transcription does. And it also leaves out the italic parts Ad Historiarum lucem (In light of History) and Cum Privilegiis Caesareo & Regio (With Imperial and Royal Privilege). Again, such information could be very interesting to book historians, including the fact that italic type is used on the front page (again a matter of layout which could be construed as visual marketing).

Also, when we look at the date, we notice this has been interpreted rather than transcribed. The Roman numeral (with the typical dots) has been silently turned into ‘1596’. This does injustice to the fact that humanists like Lipsius used Roman numerals on their title pages as a conscious imitation of ancient Roman epigraphy. The same goes for the line breaks.

Furthermore, we see that copy specific information, such as the stamp in the upper right corner and the pasted on inscription on the bottom have also been left out.

On the other hand, there is also more information in the descriptive metadata than is on the title page. The names of the illustrators, for instance, and the name of Christopher Plantin’s widow are added. In other words, the descriptive metadata covers a wide region of information about an object, possibly even information that is not explicity present in the object itself.

Worldcat¶

Let’s compare STCV’s catalogue entry with the entry for the same title in Worldcat, the world’s largest network of library content and services:

Category |

Metadata |

|---|---|

Title |

Ivsti LipsI Poliorcetic[o]n, sive, De machinis, tormentis, telis, libri qvinqve : ad historiarum lucem. |

Author |

Justus Lipsius; Petrus van der Borcht |

Publisher |

Antverpiæ : Ex Officina Plantiniana, apud Viduam, & Ioannem Moretum, M.D. XCVI [1596] |

The information is pretty similar, but now that we are tuned into some of the subtleties we notice the differences.

“Ad historiarum lucem” is present here, for instance. On the other hand, Worldcat has different capitalization and provides only one illustrator, without specifying that this is external information (i.e. not included in the title page). Worldcat also opts for a transliteration in Latin alphabet for Lipsius’s “macaronic” form Poliorceticωn, again a conscious effort of antiquarian Spielerei.

Discussion¶

These difference between a book object and various sources of descriptive metadata can be explained from the use of different cataloguing rules. Indeed, it is impossible to simply catalogue at book title (or indeed any item, be it physical or digital) “as is”. However diplomatic and inclusive you try to be when cataloguing, you will always have to make hard decisions about how to handle layout, how to transcribe characters, whether or not to standardize spelling, punctuation, etcetera.

All of this is perfectly understandable and in general (good) catalogues will be explicit and very scrupulous in the cataloguing rules they follow. The danger is that when we leave the cataloguing context and, for instance, acquire catalogue information in a data dump (STCV is freely available here) we tend to forget this and take the metadata at face value.

Imagine for a minute that you hadn’t seen the above title page, but merely got the STCV metadata from a SQL query. How accurate would your understanding of this title page actually be? And what happens when, as good DH research is bound to do, you break open metadata containers and aggregate metadata, for instance merging several of the national “short-title catalogue” initiatives (STCV, STCN, ESTC, USTC, …), which all adhere to different rules?

To make matters worse, our example was a very simple one really. There are many, even more complex metadata problems. Just to give you a taste:

How would you catalogue one of those squeeky toddler books that feature not a single word of text (no author, title, date, publisher, …)?

When in 1993 Prince changed his stage name to the unpronounceable symbol

(known to fans as the “Love Symbol”), and was sometimes referred to as the “Artist Formerly Known as Prince”, “The Artist” or “TAFKAP”, how were record shops supposed to catalogue his albums? Remember, in those days, most people would go up to the “P” section and browse for “Prince”!

(known to fans as the “Love Symbol”), and was sometimes referred to as the “Artist Formerly Known as Prince”, “The Artist” or “TAFKAP”, how were record shops supposed to catalogue his albums? Remember, in those days, most people would go up to the “P” section and browse for “Prince”!Or what about the IMDB website listing the actors of the Blair Witch Project as “missing, presumed dead” in the first year of the film’s availability (see this article)?

Metadata 101¶

We now have a better understanding of metadata. We know know that, as a former student of mine (@Karolingva) once tweeted from a RightsCon conference: metadata is not just data about data, but

created data about data

by humans

with a purpose

according to certain standards

This means than when working with metadata we need to be acutely aware of this context.

In short, that means having an understanding of cataloguing standards, metadata standards and exports.

Cataloguing standards¶

As we saw in the case of STCV or WorldCat book titles were catalogued following certain rules. The same holds true for all sorts of physical or digital items. So if you are working with metadata you’ll do well to have at least a basic understanding of the cataloguing standards that were used to create the metadata.

As for book cataloguing standards, for instance, we can mention

RDA (Resource Description and Access)

(subscription needed)

E.g. names with articles = ‘The Hague’ NOT ‘Hague, the’

DCRM(B) (Descriptive Cataloging of Rare Materials - Books)

(open source)

E.g. no spaces for abbreviations = ‘Ad S.R.E. Cardinalem’, EXCEPT multiple letter-abbreviations = ‘Ad Ph. D. Jacobum’

Metadata standards¶

Once metadata has been produced according to certain cataloguing rules, we can also define a metadata standard, i.e.

a requirement which is intended to establish a common understanding of the meaning or semantics of the data, to ensure correct and proper use and interpretation of the data by its owners and users.

Some of the most common metadata standards in the world of GLAM (galleries, libraries, archives, and museums) are:

Books: MARC

Machine-Readable Cataloging (MARC21)

e.g. field 245 = title

Archives: EAD

Encoded Archival Description (XML standard)

Objects: Dublin Core

Dublin Core Metadata Initiative

If you’re interested to know more about metadata standards, good starting points are this page by Lyrasis, a non-profit organization whose mission is to support enduring access to the world’s shared academic, scientific and cultural heritage through open technologies, and BARTOC, the Basic Register of Thesauri, Ontologies & Classifications.

Open Data¶

Working with metadata one is quickly faced with the issue of data being locked away in a so-called information silo:

an insular management system in which one information system or subsystem is incapable of reciprocal operation with others that are, or should be, related. Thus information is not adequately shared but rather remains sequestered within each system or subsystem, figuratively trapped within a container like grain is trapped within a silo: there may be much of it, and it may be stacked quite high and freely available within those limits, but it has no effect outside those limits. Such data silos are proving to be an obstacle for businesses wishing to use data mining to make productive use of their data.

Luckily many information systems, for instance for GLAM institutions, are paying increasing attention to providing metadata as open data, which in turn allows to aggregate it (for further information retrieval, research purposes, etcetera).

Such initiatives will make metadata available in all sorts of standards (see above) and formats, such as data dumps in .txt or .tab, structured formats like .csv, document databases like .xml or .json, or Linked Data. As we have seen in the previous chapter with CERL and Europeana, some institutions even provide an API.

Examples for book history¶

Some time ago I made a very incomplete of useful metadata sources in the field of book history. They might be of interest when your research takes you that direction.

Biographic databases

VIAF (Virtual International Authority File) (SRU)

DBpedia (SPARQL endpoint, Lookup/Search API)

CERL thesaurus (place name and personal names in Europe in the period of hand press printing, c. 1450 - c. 1830) (SRU)

Europeana APIs (SPARQL endpoint, REST API, …)

RKDArtists (biographical data about artists, companies and institutes of various disciplines of visual arts, applied arts and architecture from both the Netherlands as abroad) (API with Lucene query syntax)

Bibliographic databases

Worldcat (wide range of exports, plugins, APIs)

Anet open data (including STCV, downloads in MARCXML or SQLite)

STCN (SPARQL endpoint)

ESTC (R toolkit)

HPB (Heritage of the Printed Book Database, a catalogue of European printing of the hand-press period, c.1455-c.1830) (SRU)

TW (Typenrepertorium der Wiegendrucke) (XML exports)

DH examples¶

As an example of the kind of DH research you could do using library metadata, I refer to a kind of proof-of-concept paper of mine: A Datamining Approach to the Anet Database of Hand Printed Books. The Case of Early Modern Quiring Practices, which specifically aims to analyse the Early Modern practice of ‘quiring’ gatherings in handpress book production.

Another, more recent project was Ulpia, an aggregator of rare book databases that uses SRU, OAI-PMH (see below) and other APIs. Ulpia is serverless, i.e. it does not give you the requested information by performing the queries on a server, but the queries are run in your client’s browser. In this way, Ulpia is a discovery tool, meant to help identify or locate rare books, and start the bibliographic journey, rather than get detailed metadata (for which the individual databases are better suited).

Exercise: MARC21 to Dublin Core conversion for OAI-PMH¶

The Open Archives Initiative Protocol for Metadata Harvesting (OAI-PMH) or OAI for short:

is a low-barrier mechanism for repository interoperability. Data Providers are repositories that expose structured metadata via OAI-PMH. Service Providers then make OAI-PMH service requests to harvest that metadata. OAI-PMH is a set of six verbs or services that are invoked within HTTP.

The verbs are:

Identify

ListMetadataFormats

ListIdentifiers

ListRecords

ListSets

GetRecord

Knowing SRU from the above, OAI-PMH is similar as an architecture, except the fact that it does not natively support a query language. (Although you can implement querying by defining “sets”).

At Anet, for instance, we provide full OAI access to our complete database of books. Like so:

(MARC21)

https://anet.be/oai/catgeneric/server.phtml?verb=GetRecord&metadataPrefix=marc21&identifier=c:lvd:123456

(MODS)

https://anet.be/oai/catgeneric/server.phtml?verb=GetRecord&metadataPrefix=mods&identifier=c:lvd:123456

In these examples, the trailing c:lvd: number is a unique Library Object Identifier (LOI) used by our LMS Brocade. You can substitute it for any LOI you find in our OPAC.

Typically, libraries will use the OAI protocol to import/export metadata in different formats. So when they set up an OAI server, one of the main tasks is making software that converts data from one standard to another. Library management systems, for instance, need such conversions both to be able to feed an OAI server from their own database respository, or, vice versa, to harvest data from external repositories and convert it to the standard(s) they use.

According to the standard’s specification, all implementations of OAI-PMH must support representing metadata in Dublin Core, so the task here is to write a metadata converter that is able to harvest MARC21 metadata (XML) and convert that to Dublin Core (XML). It should be a Python application that asks for a LOI number (e.g. c:lvd:123456), uses OAI to harvest the MARC21 metadata and then writes the Dublin Core conversion to a file (e.g. 123456.xml).

XML namespaces¶

Upon closely inspecting the OAI-PMH XML response from the examples cited above, you will notice that the root element has a special structure:

<OAI-PMH xmlns="http://www.openarchives.org/OAI/2.0/" xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xsi:schemaLocation="http://www.openarchives.org/OAI/2.0/ http://www.openarchives.org/OAI/2.0/OAI-PMH.xsd">

The attribute xmlns declares an XML namespace, which is a way to avoid element name conflicts (for instance when combining XML) by using a prefix. This means that if we want to access this element or one of its sub-elements, we will always have to include the prefix. There are different ways of doing this. LXML uses curly braces for this:

...

# raw string is safer for XML namespaces

for datafield in root.iter(r"{http://www.openarchives.org/OAI/2.0/}datafield"):

...

For more information, you can look at this tutorial from w3schools and the info from the lxml module.

Tips¶

You can use the Library of Congress MARC to Dublin Core Crosswalk. You may limit yourself to the fields mentioned in the “unqualified” table and skip the “Leader” field. You will find the meaning of the various codes (

a,c, etcetera) in the MARC specification, but you can limit yourself to codea, unless the crosswalk explicitly mentions other codes (e.g.260=Publisher).