Chapter 1: Welcome¶

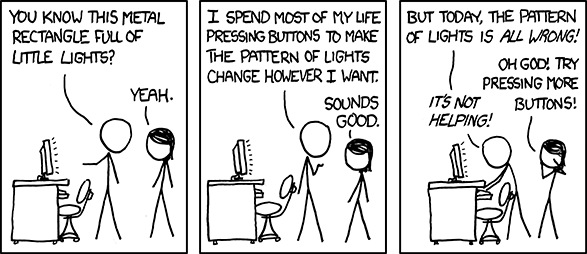

Credit: xkcd

TL;DR: This is a course on Information Science made by a classicist turned software engineer

Welcome¶

Welcome to the course “Information Science” for the University of Antwerp Master of Digital Text Analysis!

Who am I and why does that matter?¶

Who am I?¶

My name is Tom Deneire and I work as a software engineer.

However, my carreer did not start in IT. On the contrary, I studied Classics (MA 2003, PhD 2009) and was active in humanities research and education for quite some time.

From 2009-2013 I worked in academia as a postdoctoral researcher (Neo-Latin Studies) and a visiting professor (Latin rhetoric and stylistics), focussing mainly on the interplay of Neo-Latin and the vernacular, literary theory and dabbling in (then emerging) Digital Humanities (see e.g. Deneire 2018).

In 2013 I moved to the library world (University Library of Antwerp) as Curator of the Special Collections, where I became increasingly interested in library metadata and data science. I learned the basics of XML, SQL and Python, and started using these tools to research and aggregate library metadata.

In 2018 this lead to a switch from the Special Collections to the library’s software department Anet, where I currently work as a full-stack engineer on a product called Brocade Library Services. My current project is a complete rewrite and integration of the library’s two modules for authority control.

My technology stack mainly includes Python, Go and especially MUMPS, the language for our database engine (GT.M, provided by YottaDB). However, I also use SQL, HTML/CSS, Javascript and PHP. My OS of choice is Linux (i.c. the Linux Mint distro) and I use Neovim for an editor.

Why does that matter?¶

This should make clear that I am not an academic expert in Information Science, nor have I been a professional developer for a long time. Indeed, at first I was not sure if I am the best person to teach this course! So it goes without saying that I will certainly not have all the answers.

On the other hand, my profile is very kindred to that of my intended audience, which I think of as humanities majors looking to acquire digital skills. I hope this common perspective will enable me to teach what such students need most from a vast field such as Information Science.

Contents and learning outcomes¶

My specific profile also implies that this will not be a standard introduction to Information Science. If this is really what you are after, there is enough literature out there to acquire this knowledge by yourself.

Instead what is offered here is a very hands-on introduction into information science and the technologies used in the field. Think of this class as an internship with an information systems company, rather than an academic course. The aim of this course is to provide you with a minimum of theoretical knowledge and a maximum of practical experience.

The course will discuss the following information science topics:

Definition, history, ethics

Encoding

Databases

Querying

Metadata

Indexing

Searching

Architecture

In line with the hands-on nature of this course, most chapters will feature a code exercise, designed to offer a realistic example of a real-world implementation of the technology discussed in the chapter.

Reading¶

Required¶

Given the very applied nature of this course, I feel it is necessary to supplement it with a brief theoretical introduction to the topic of information. To meet that goal, this course requires reading chapters 1-7 of this highly readable book:

Foundations of Information, by Amy J. Ko (2021), available as a free e-book and GitHub repository

Optional¶

If a subject of this course is of particular interest to you, you can find more information about the various topics in the following publications:

Handbook of Information Science, By Wolfgang G. Stock, Mechtild Stock, (Berlin: De Gruyter Saur, 2013), ISBN 978-3110234992, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110235005

The Myth and Magic of Library Systems, By Keith J. Kelley, ISBN 978-0081000762

Modern Information Retrieval: The Concepts and Technology behind Search, By Ricardo Baeza-Yates, Berthier Ribeiro-Neto, Second edition (Harlow e.a.: Addison-Wesley, 2011), ISBN 978-0-321-41691-9

Information Architecture, 4th Edition, By Louis Rosenfeld, Peter Morville, Jorge Arango, ISBN 978-1491911686

A Librarian’s Guide to Graphs, Data and the Semantic Web, By James Powell, ISBN 978-1843347538

Apprenticeship Patterns, By Dave Hoover, Adewale Oshineye, ISBN 978-0596518387

Other resources¶

While this course is designed for beginners, it may still be possible that you feel your knowledge about a certain topic is lacking, especially when it comes to certain technological concepts. If so, the Internet offers a vast array of resources designed to help your learning process.

For me, one of the best resources for self-improvement is Medium, an online publishing platform for blogs dealing with just about anything, but with a strong emphasis on software and technology. Medium lets you configure your interests so you get a personalized list of reading suggestions. Most articles on Medium are free and the site also allows you to read up to 3 premium articles for free every month. Personally, I find a paying membership more than worthwile.

Other good, free resources include:

Finally, if you’re looking for more hands-on introductions to topics similar to those treated in this course, you might want to have a look at Library Carpentry, a non-profit organization who offer free online workshops teaching technical skills for people working in library- and information-related roles (UNIX shell, Git, Python, R, XML, …).

Technical requirements¶

This course is available as a series of Jupyter Notebooks and published on the GitHub repository for this course.

To view the content without code execution, you can:

Read the notebooks as a Jupyter Book hosted on GitHub Pages

Read the notebooks in the GitHub repository

To view the content with code execution, you can:

Use an editor with a Jupyter Notebook extension, such as VS Code

Install Jupyter (Lab or Notebook) locally and open the notebooks in your browser

If you don’t want to install Jupyter on your machine, you can open the notebooks with Google Colab, but executing the code isn’t always guaranteed to work (because of missing third-party libraries and stack overflows in heavy data operations).

The best way to obtain these course materials on your local machine is to:

Install

giton our local machineGet a GitHub account (if you don’t already have one)

Fork this repo to your own GitHub account

Clone the repo to your local machine

And of course if you find errors in the other course materials or want to propose changes or additions, I am very open to pull requests.

Git help!¶

If you’re unsure how to do all of this, this GitHub guide will help.

Other interesting sources on Git are this Medium article and Atlassian’s tutorial. This Medium article contains even more references to cheatsheets, tutorials, etc.

Bear in mind that you can use Git from the command line (which I would always advise in the learning stages), but that there are also desktop applications, such as GitHub Desktop, GitKraken or integrations for your editor, such as GitLens for VSCode.