Chapter 8: Searching Information¶

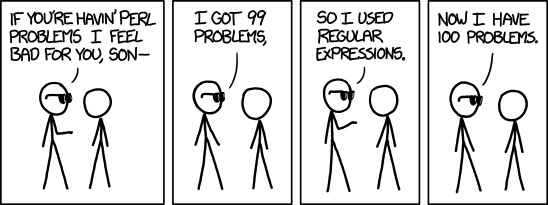

Credit: xkcd.com

TL;DR: Searching information can happen in a variety of ways; either exact or fuzzy.

Introduction¶

In the previous chapter we went from searching to indexing rather quickly. In fact, although we acknowledged that searching is a discrete field of computer science, we limited our practical discussion of it to an example of the .find() string method in Python!

However, we have already seen that searching text is rarely as easy as that. Searching vast data sets lead us to indexing, as did the issue of complex searches, such as Boolean queries. Moreover, not all searching tasks can be solved with indexing. Sometimes we want to include wildcards (you are probably familiar with the * and ? symbols) and will need to use regular expressions in our search, while other times we are not looking for exact results, but more interested in fuzzy searching.

Regular expressions¶

The * symbol we used is actually part of a separate programming language, called regular expressions. Wikipedia:Regular_expression says:

A regular expression (shortened as regex or regexp; also referred to as rational expression) is a sequence of characters that define a search pattern. Usually such patterns are used by string-searching algorithms for “find” or “find and replace” operations on strings, or for input validation. It is a technique developed in theoretical computer science and formal language theory.

The concept arose in the 1950s when the American mathematician Stephen Cole Kleene formalized the description of a regular language. The concept came into common use with Unix text-processing utilities. Different syntaxes for writing regular expressions have existed since the 1980s, one being the POSIX standard and another, widely used, being the Perl syntax.

Regular expressions are used in search engines, search and replace dialogs of word processors and text editors, in text processing utilities such as sed and AWK and in lexical analysis. Many programming languages provide regex capabilities either built-in or via libraries.

Python uses the Perl regex syntax, as do, for instance, Java, JavaScript, Julia, Ruby, Microsoft’s .NET Framework, and others. Some environments actually let you choose the regex syntax you want to use, like PHP or the UNIX grep command.

Regular expressions are an extremely powerful tool, but as the above cartoon shows there is a downside too. It is sometimes said that regular expressions are a write only programming language, as the code is often hardly readable, especially if you revisit a regex written long ago. Moreover, regular expresssions can be very tricky, for example, when they provide exact matches in your tests, only to produce mismatches when you open up the use cases.

Consider this example:

import re

rhyme = re.compile(r'\Dar')

my_text = "Let's look at the words bar, car, tar, mar and far"

print(re.findall(rhyme, my_text))

['bar', 'car', 'tar', 'mar', 'far']

So I’m looking for potential rhymes on “bar” and have written a regex that looks for one letter character \D followed by ar. However, when you apply this to one of the paragraphs you quickly see some mismatches, as we forgot to specify that the pattern can only occur at the end of a word.

paragraph = "Regular expressions are an extremely powerful tool, but as the above cartoon shows there is a downside too. It is sometimes said that regular expressions are a write only programming language, as the code is often hardly readable, especially if you revisit a regex written long ago. Moreover, regular expresssions can be very tricky, for example, when they provide exact matches in your tests, only to produce mismatches when you open up the use cases."

print(re.findall(rhyme, paragraph))

['lar', ' ar', 'car', 'lar', ' ar', 'har', 'lar']

So when you are inclined to use regular expressions, it is often good to ask yourself: is this the best solution for this problem? If you find yourself parsing XML with regular expressions (use a parsing library!), or testing the type of user input with regexes (use .isinstance()), reconsider!

The only way to really get the hang of regular expressions is by diving in the deep end. Fortunately, there are many good tutorials online (e.g. at w3schools) and there are also handy regex testers where you can immediately check your regex, like regexr. For a good Python cheat sheet, see this Medium post.

A good and certainly not trivial exercise would be to write a regex that can detect a valid email address, as specified in RFC 5322. For a (more readable) summary, see Wikipedia:Email_address#Syntax.

In practice, most applications that ask you to enter an email address will check on a simple subset of the specification. Can you whip something up that passes this test?

import re

# Examples from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Email_address#Examples

TEST = {

# valid addresses

"simple@example.com": True,

"very.common@example.com": True,

"disposable.style.email.with+symbol@example.com": True,

"other.email-with-hyphen@example.com": True,

"x@example.com (one-letter local-part)": True,

"admin@mailserver1": True, # local domain name with no TLD, although ICANN highly discourages dotless email addresses

# invalid_addresses

"Abc.example.com": False, # no @ character

"A@b@c@example.com": False, # only one @ is allowed outside quotation marks

"1234567890123456789012345678901234567890123456789012345678901234+x@example.com": False, # local part is longer than 64 characters

"i_like_underscore@but_its_not_allow_in_this_part.example.com": False # underscore is not allowed in domain part

}

def email_regex(address: str) -> bool:

# expand pattern

pattern = r'.*?@.*?'

if re.search(pattern, address):

return True

else:

return False

for case in TEST:

result = email_regex(case)

if not result == TEST[case]:

print(f"Test failed on {case}. Expected = {TEST[case]}. Result = {result}")

Test failed on A@b@c@example.com. Expected = False. Result = True

Test failed on 1234567890123456789012345678901234567890123456789012345678901234+x@example.com. Expected = False. Result = True

Test failed on i_like_underscore@but_its_not_allow_in_this_part.example.com. Expected = False. Result = True

Fuzzy searching¶

Regular expressions can also be used to illustrate the concept of fuzzy searching or approximate string matching, which is the technique of finding strings that match a pattern approximately rather than exactly. Wikipedia:Approximate_string_matching explains:

The closeness of a match is measured in terms of the number of primitive operations necessary to convert the string into an exact match. This number is called the edit distance between the string and the pattern. The usual primitive operations are:

insertion: cot → coat

deletion: coat → cot

substitution: coat → cost

These three operations may be generalized as forms of substitution by adding a NULL character (here symbolized by

*) wherever a character has been deleted or inserted:

insertion: co*t → coat

deletion: coat → co*t

substitution: coat → cost

Some approximate matchers also treat transposition, in which the positions of two letters in the string are swapped, to be a primitive operation.

transposition: cost → cots

Different approximate matchers impose different constraints. Some matchers use a single global unweighted cost, that is, the total number of primitive operations necessary to convert the match to the pattern. For example, if the pattern is coil, foil differs by one substitution, coils by one insertion, oil by one deletion, and foal by two substitutions. If all operations count as a single unit of cost and the limit is set to one, foil, coils, and oil will count as matches while foal will not.

Other matchers specify the number of operations of each type separately, while still others set a total cost but allow different weights to be assigned to different operations. Some matchers permit separate assignments of limits and weights to individual groups in the pattern.

String metrics¶

As a concrete example of a string matcher, we can have a look at string metrics.

A string metric (also known as a string similarity metric or string distance function) is a metric that measures distance (“inverse similarity”) between two text strings. A string metric provides a number indicating an algorithm-specific indication of distance. The most widely known string metric is a rudimentary one called the Levenshtein distance (also known as “edit distance”).

Another is the Jaro-Winkler distance, which is perhaps a bit easier to grasp. The lower the Jaro-Winkler distance for two strings is, the more similar the strings are. The score is normalized such that 1 means an exact match and 0 means there is no similarity. For a Python implementation of the Jaro-Winkler similarity, which is a modified version of the Jaro-Winkler distance, giving more favorable ratings to strings that match from the beginning, see the course repository.

There are many concrete applications for string metrics. Think of Google’s Did you mean… feature, which is a form of fuzzy searching, or, the example used below, a spelling checker.

Final remark¶

With the discussion of searching, we come to the end of our very succinct overview of Information Science.

Had our topic been Information Retrieval, we would have needed to add two additional, crucial steps, i.e. the evaluation and ranking of the search results. This articulates the difference between database querying, with results in data, and information retrieval querying, which results in documents containing data. In order to sift through the search results of the latter, we need evaluation measures and ranking to make the results usable. Unfortunately, evaluation and ranking are beyond the scope of this course.

Exercise: Spelling checker¶

One very practical application of string metrics, search evaluation and ranking is writing a spelling checker.

I’m not going to reveal too much of the solution here, but what I can say is that you’ll definitely need two things:

A dictionary of existing words. As the corpus of the dictionary you can use the collection of words found in the British fiction corpus from the previous chapter. This is limited, but it’ll do for now.

A string metric. For this, you can use the Jaro-Winkler metric, which you do not have to implement yourself. Instead just use the code supplied in

jarowinkler.pyas shown below.

Your application should do two things:

Build the dictionary and save it in some form so it does not have to be rebuilt every time when the application is used.

Take a string and print on standard output a list of potential spelling mistakes, with a limited number of suggestions for the correction.

As a final tip, you should consider reusing some of your code from chapter 3 for this application…

from jarowinkler import jaro_winkler

print(jaro_winkler("coat", "cot"))

0.9333333333333333