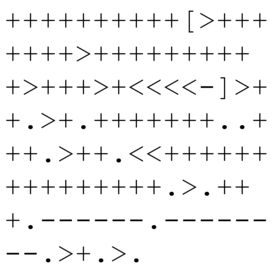

Chapter 3: Encoding Information¶

“Hello world” program in Brainfuck

TL;DR: There is no such thing as pure information. Information is encoded and needs to be decoded and manipulated before use.

Manipulating Information¶

Let’s go back to Paul Otlet and his index cards for a minute. For me, one of the key takeaways of this story is the simple fact that information never just is. Even when we think we are merely making it accessable through catalogs or search engines, information is, as the postmodern philosopher Jacques Derrida would say, always already manipulated.

So we could say that at the heart of information retrieval is manipulating information, i.e. selecting, grouping, filtering, ordering, sorting, ranking. In fact, select, group, filter, order, sort and rank are the most important keywords in the world’s most used database query language, SQL, which we will talk about later.

In programming terms, this manipulation often boils down to basic string operations, like filtering strings on the presence of substrings, grouping or sorting them. And while manipulating strings might seem easy, things can get complicated really easily.

Sorting strings¶

Let’s look at the example of sorting strings. Suppose our task is presenting an alphabetized list of contact persons.

Of course, in Python you can just do this:

contacts = ["Doe, John", "Poppins, Mary", "Doe, Jane"]

sorted_contacts = sorted(contacts)

print(sorted_contacts)

['Doe, Jane', 'Doe, John', 'Poppins, Mary']

But suppose you are dealing with a programming language where there is no built-in sorting method. (And believe me, there are!) How would you go about sorting a list of strings?

The key to this problem is that in computing there really is no such thing as characters. All characters are represented by some numerical value and various sorting algorithms use these values to implement string sorting.

This takes us to the issue of encoding, which is at the heart of all things digital.

Encoding¶

Encoding is not an easy concept to wrap your head around. When I first started out programming, I took me quite some time to really grasp it (and when I finally did, I wrote a blog post Text versus bytes about it). So let’s see if we can come to understand it.

Ones and zeros¶

A computer is an electronic device, which really only “understands” on and off. Think of how the light goes on and off when you flip the switch. In a way, a computer is basically a giant collection of light switches.

This is why a computer’s processor can only operate on 0 and 1, or bits, which can be combined to represent binary numbers, e.g. 100 = 4. It is these binary numbers that the processor uses as both data and instructions (a.k.a. “machine code”).

It makes sense to group bits into units; otherwise, we would just end up with one long string of ones and zeros and no way to chop it up into meaningful parts. A group of eight binary digits is called a byte, but historically the size of the byte is not strictly defined. In general, though, modern computer architectures work with an 8-bit byte.

Bytes¶

This binary nature of computers means that on a fundamental level all data is just a collection of bytes. Take files, for instance. In essence, there’s no difference between a text file, an image or an executable. So it’s actually a bit (pun not intended) confusing when people talk about the “binary” files, i.e. not human-readable, as opposed to human-readable “text”.

Let’s look at an example myfile:

$ xxd -b myfile

00000000: 01101000 01100101 01101100 01101100 01101111 00100000

00000006: 01110111 01101111 01110010 01101100 01100100 00001010

The instruction xxd -b asks for a binary “dump” of myfile.

We see that it contains 12 eight-bit bytes. Because the binary representation is difficult on the eyes, bytes are often displayed as hexadecimal numbers:

$ xxd -g 1 myfile

00000000: 68 65 6c 6c 6f 20 77 6f 72 6c 64 0a

Or (less often) as decimal numbers:

$ od -t d1 myfile

0000000 104 101 108 108 111 32 119 111 114 108 100 10

In decimals, 8-bit bytes go up to 256, which makes sense as 2⁸ = 256, i.e. eight positions can hold either zero or one, which equals 256 combinations.

But how do we know what these bytes represent?

Character encoding¶

In order to interpret bytes in an meaningful way, for instance to display them as text or as an image, we need to give the computer additional information. This is done in several ways, one of which is predetermining the file structure with identifiable sequences of bytes.

Another is specifying an encoding, which you can think of as a lookup table connecting meaning to its corresponding digital representation. When it comes to text, we call this “character encoding”. Turning characters into code is referred to as “encoding”, interpreting code as characters is “decoding”.

One of the earliest character encoding standards was ASCII, which specifies that the character a is represented as byte 61 (hexadecimal) or 97 (decimal) or 01100001 (binary). However, since 8-bit bytes only give you 256 possibilities, today multibyte encodings are used. In the past, different areas of the world used different encodings, which was software’s Tower of Babel, causing a bunch of communication problems to this day. Luckily, today UTF8 is more or less the international standard — for instance, accounting for 97% of all web pages. UTF-8 is capable of encoding all 1,112,064 valid character code points in Unicode using one to four one-byte units.

Bytes as text¶

Going back to our file, we can now ask the computer to interpret these bytes as text. It is important to realize that any time we display bytes as text, be it in a terminal, a word processor, an editor or a browser, we need a character encoding. Often, we are unaware of encoding that is used, but there is always a choice to be made, whether by default settings or by some clever software that tries to identify the encoding.

Terminals, for instance, have a default character setting — mine is set to UTF-8. So when we ask to print myfile we see this:

$ cat myfile

hello world

This means the bytes we discussed earlier are the UTF-8 representation of the string hello world. For this example, other character encodings, like ASCII or ISO-Latin-1 would yield the same result. But the difference quickly becomes clear when we look at another example.

Let’s save the UTF-8 encoded text string El Niño as a file and then print it. We can do that in the terminal — remember, it’s set to UTF-8 display by default:

$ echo "El Niño" > myfile

$ cat myfile

El Niño

Now let’s change the terminal’s encoding to CP-1252 and see what happens when we print the same file:

$ cat myfile

El Niño

We call this Mojibake; the garbled text that I’m sure you’ve often seen under the form of the generic replacement �. But do you understand why this happens? Because myfile contains bytes entered as UTF-8 encoded text, displaying the same

bytes in another encoding doesn’t give the result we expect.

This is also explains why commands like cat don’t work on so-called binary files, or opening them in an editor reveals only gibberish: they’re not encoded as text.

Text as bytes¶

The example of El Niño shows that we can also take text — a string typed in a terminal — and use that as bytes. For instance, when we save text from an editor in a file. At first, this can be a tricky concept to wrap your head round. Bytes can be strings and strings are bytes. The important thing to remember is that whenever you handle text or characters, there is an (explicit or implicit) encoding at work.

When you think of it, code is text too, so some programming languages make certain encoding assumptions as well. Others just deal with text as bytes and leave the encoding up to other applications (such as a browser or a terminal).

Go, for instance, is natively UTF-8, for instance, which means you can do this:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fmt.Println("Hello, 世界")

}

Python 3 is UTF-8 too, but Python 2 used to be ASCII. So, regardless of whether your code editor is able to display such a string or not, the Python 2 will complain if you try to use the print function on it. Remember, print tells a device to display bytes. So if you put this in a file test.py

print "Hello, 世界"

and execute it with Python 2, it will throw the following error.

py2 test.py

File "test.py", line 1

SyntaxError: Non-ASCII character '\\xe4' in file test.py on line 1, but no encoding declared; see http://python.org/dev/peps/pep-0263/ for details

The bottom line is that you should always be careful when handling text and when in doubt use explicit encoding or decoding mechanisms.

Handling multibyte characters¶

There’s a lot more to say about character encodings, but I’ll wrap things up with an observation about multibyte characters that might prompt you to study the subject more in depth.

A popular question in code interviews is to ask the candidate to write (pseudo-)code to reverse a string. In Python, for instance, there is a nice oneliner for this, which uses a slice from end to start (::) that steps backward (-1):

print("Hello World"[::-1])

dlroW olleH

Yet think about what happens under the hood. Apparently, there is a mechanism that iterates over the bytes that make up the string and reverses their order. But what happens when a character is represented by more than one byte? For instance, 界 , is four bytes in UTF-8 (e7 95 8c 0a in hex. The first of these is a leader byte, a byte reserved to start a specific multibyte sequence, the other three are continuation bytes, which are only valid when preceded by a

leader. So when you reverse these bytes, you end up with a different byte sequence, which is actually invalid UTF-8!

Fortunately, Python (which is natively UTF-8, remember) is able to handle this

print("Hello, 世界"[::-1])

界世 ,olleH

In other programming languages, though, you would have to write a function that identifies byte units in the string and then reverse their order, not the bytes themselves. Which would imply knowledge of the string’s encoding…

Conclusion¶

Text versus bytes is a complex issue that even advanced programmers can struggle with, or have tried to avoid for most of their careers. However, it is a fascinating reminder of the very essence of computing and understanding it, or at least the fundamentals, is really indispensable for any software developer.

Unicode¶

Now that we have a better understanding of encoding, let’s go back to our sorting example, and consider the application of Unicode code points for mapping characters to numerical values. In Python we can use the function ord() to get a character’s decimal Unicode code point:

for char in "Doe, John":

print(ord(char), end=",")

68,111,101,44,32,74,111,104,110,

So far so good, it seems. But matters quickly get complex. One example is the difference between upper and lower case:

for item in ["doe, john", "DOE, JOHN"]:

for char in item:

print(ord(char),end=",")

print("\n")

100,111,101,44,32,106,111,104,110,

68,79,69,44,32,74,79,72,78,

You can account for that by converting all strings to lower case before sorting, but what happens in the case of the French Étienne versus Etienne, which you would want to be sorted close to each other and are, in fact, used interchangeably?

for char in "Étienne".lower():

print(char + " = " + str(ord(char)), end=" ,")

print("\n")

for char in "Etienne".lower():

print(char + " = " + str(ord(char)), end=" ,")

é = 233 ,t = 116 ,i = 105 ,e = 101 ,n = 110 ,n = 110 ,e = 101 ,

e = 101 ,t = 116 ,i = 105 ,e = 101 ,n = 110 ,n = 110 ,e = 101 ,

We can complicate matters even more:

print('\u00C5')

print('\u212B')

print('\u0041\u030A')

Å

Å

Å

This example shows that even Unicode code points don’t offer a unique mapping of characters to numbers. Luckily, to solve this, there is something called Unicode normalization.

Decoding¶

It is important to realize that all text-oriented interfaces that you use to display text will make implicit or explicit assumptions about the encoding of texts. Whether it is your terminal environment, the editor you use (e.g. VSCode) or even a programming language, you need to be aware of such default encodings.

For instance, Python3 (not Python2) is default UTF8. So if you receive strings in a different encoding, which will happen in real-life applications like scraping text from the internet, you’ll have to decode them with the proper codec to render your results properly.

Let’s simulate what would happen if you were working with non-UTF8 encoded strings in Python3 and decode them with the default codec

e_accent_aigue = chr(233) # unicode code point for é character

for encoding in ['utf8', 'latin1', 'ibm850']:

bytes_string = e_accent_aigue.encode(encoding=encoding)

print(bytes_string)

try:

print(bytes_string.decode()) # the default is equal to .decode(encoding='utf8')

except UnicodeDecodeError:

print(f"Unable to print bytes {bytes_string} in UTF8")

b'\xc3\xa9'

é

b'\xe9'

Unable to print bytes b'\xe9' in UTF8

b'\x82'

Unable to print bytes b'\x82' in UTF8

You can see how complex seemingly trivial tasks of information theory, like alphabetizing a list, really are. We’ve gone from Paul Otlet’s grand visions of the future to the nitty-gritty bits and bytes, one of the most fundamental concepts in computer science, really quickly.

Exercise: Onegram Counter¶

You probably know about Google Book’s Ngram Viewer: when you enter phrases into it, it displays a graph showing how those phrases have occurred in a corpus of books (e.g. “British English”, “English Fiction”, “French”) over the selected years.

The code example for this chapter is building a Python function that can take the file data/corpus.txt (UTF-8 encoded) from this repository as an argument and print a count of the 100 most frequent 1-grams (i.e. single words).

In essence the job is to do this:

from collections import Counter

import os

def onegrams(file: str) -> Counter:

"""

Function that takes a filepath as argument

and returns a counter object for onegrams (single words)

"""

with open(file, 'r') as corpus:

raw_text = corpus.read()

# .casefold() is better than .lower() here

# https://www.programiz.com/python-programming/methods/string/casefold

normalized_text = raw_text.casefold()

words = normalized_text.split(' ')

return Counter(words)

CORPUS = os.path.join('data', 'corpus.txt')

ngrams = onegrams(CORPUS)

print(ngrams.most_common(100))

[('the', 11852), ('', 5952), ('of', 5768), ('and', 5264), ('to', 4027), ('a', 3980), ('in', 3548), ('that', 2336), ('his', 2061), ('it', 1517), ('as', 1490), ('i', 1488), ('with', 1460), ('he', 1448), ('is', 1400), ('was', 1393), ('for', 1337), ('but', 1319), ('all', 1148), ('at', 1116), ('this', 1063), ('by', 1042), ('from', 944), ('not', 933), ('be', 863), ('on', 850), ('so', 763), ('you', 718), ('one', 694), ('have', 658), ('had', 647), ('or', 638), ('were', 551), ('they', 547), ('are', 504), ('some', 498), ('my', 484), ('him', 480), ('which', 478), ('their', 478), ('upon', 475), ('an', 473), ('like', 470), ('when', 458), ('whale', 456), ('into', 452), ('now', 437), ('there', 415), ('no', 414), ('what', 413), ('if', 404), ('out', 397), ('up', 380), ('we', 379), ('old', 365), ('would', 350), ('more', 348), ('been', 338), ('over', 324), ('only', 322), ('then', 312), ('its', 307), ('such', 307), ('me', 307), ('other', 301), ('will', 300), ('these', 299), ('down', 270), ('any', 269), ('than', 262), ('has', 257), ('very', 252), ('though', 245), ('yet', 245), ('those', 242), ('must', 238), ('them', 237), ('her', 237), ('do', 234), ('about', 234), ('said', 233), ('ye', 232), ('who', 231), ('still', 229), ('great', 229), ('most', 228), ('man', 220), ('two', 219), ('seemed', 216), ('long', 214), ('your', 213), ('before', 212), ('it,', 210), ('thou', 210), ('ship', 209), ('after', 208), ('white', 207), ('did', 202), ('little', 201), ('him,', 194)]

However, there is a twist: you can’t use the collections library…

Moreover, try to think about what may be suboptimal in this example. For instance, in this code all of the text is loaded into memory in one time (with the read() method). What would happen if we tried this on a really big text file?

Most importantly, the count is also wrong. Check by counting in an editor, for instance, and try to find out why. (For instance, and actually occurs 6471 times!)

Further reading¶

If you want to get a really good idea of how complex counting words can get, you can read this blog post Performance comparison: counting words in Python, Go, C++, C, AWK, Forth, and Rust.