Chapter 7: Indexing Information¶

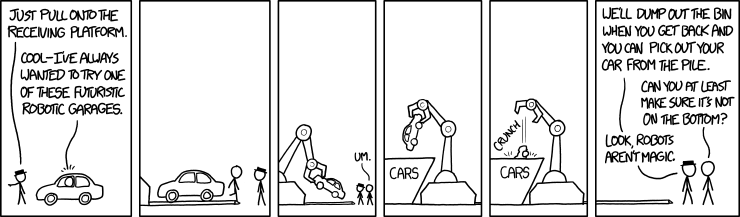

Credit: xkcd

TL;DR: There is too much data out there to search efficiently. We need indexing to speed things up.

Searching¶

In all of our discussions about information we have so far neglected perhaps the most important aspect of it: searching. Indeed, you could say that the only difference between data and information, is that “information is data that we are looking for”. Ergo, very simply said, working with information often boils down to “searching stuff”. Whether it be metadata stored in databases (e.g. searching a library catalogue), text stored in documents (e.g. a full-text search-engine for a website) or even multimedia information retrieval.

Searching and search optimization are a vast area of computer science and a distinct type of computational problem. For instance, Donald Knuth’s monumental The Art of Computer Programming devotes an entire volume (i.e. vol. 3) to “Sorting and Searching”. This means that we will only be able to briefly touch on the topic and, as always, from a very practical point of view.

Still, at face value searching might seem simple. Let’s look at finding a substring in a string. In Python, for instance, offers several ways to check for this:

MY_STRING = "Hello world, this is me"

MY_SEARCH = "me"

# one way

if MY_SEARCH in MY_STRING:

print("Found!")

else:

print("Not found")

# another way

if not MY_STRING.find(MY_SEARCH) == -1:

print("Found!")

else:

print("Not found!")

# third way

from re import search

if search(MY_SEARCH, MY_STRING):

print("Found!")

else:

print("Not found!")

Found!

Found!

Found!

However, search operations can soon become complicated and time-consuming. One crucial issue is the quantity of data we need to search. The above example could afford to use a string method to look for a literal string, but obviously this is not realistic when you are searching through millions of books (e.g. Google Books contains >40.000.000 books) or huge metadata containers (e.g. Spotify contains >70.000.000 songs).

Indexing¶

One way to deal with his issue is indexing. Simply said, an index is a data structure that improves the speed of data retrieval operations at the cost of additional writes and storage space to maintain the index data structure.

Simple searches¶

Consider the following example. Let’s say we have a large list of book titles and want to search them for a specific term.

Let’s first use SQL and the STCV database from an earlier chapter to make such a list.

import sqlite3

import os.path

import random

conn = sqlite3.connect(os.path.join('data', 'stcv.sqlite'))

c = conn.cursor()

query = "select distinct title_ti from title"

c.execute(query)

BOOK_TITLES = []

for title in c.fetchall():

BOOK_TITLES.append(*title) # `*` operator unpacks the tuple `title`

conn.close()

# length of list

length = len(BOOK_TITLES)

print(length, "titles, e.g.:")

# some examples

for _ in range(0,10):

print("-", BOOK_TITLES[random.randint(0, length)])

26153 titles, e.g.:

- Gheestelicken schat vande derde ordre S. Dominici

- Het tweede deel der meditatien

- Reghelen end oeffeninghen voor de gheestelycke dochters vanden H. Franciscus de Sales

- Translaet van het reglement raeckende d'appellatien, oft ander belagh vande ordonnantien van commissarissen tot auditie, ende recoulement vande rekeninghen vande publicque lasten, ende penninghen

- Decret rendu au conseil souverain de Brabant. Le 20 septembre 1791

- Copye van den circulairen brief, gheschreven inghevolge de orders van sijne catholiecke majesteyt, door den secretaris van de universeele depesche, aen alle sijne ambassadeurs inde uyt-heemsche hoven

- Nieuwe lijste van consumptie, [...] omme ghelicht ende ontfanghen te worden binnen den zeluen lande van Vlaendre: daermede te nieten ghedaen worden diuersche voorghaende lijsten

- Missæ propriæ sanctorum ecclesiæ cathedralis, et diœcesis Antverpiensis

- Maria Theresia [...]. Op de menighvuldige clachten [...] dat de heirbaenen, publiecke wegen, ende straeten in de seven quartieren van Antwerpen, ende in den byvanck van Lier soodaenigh verhindert, belemmert, ende buyten staet gestelt zijn, dat het [...] niet mogelijck en is [...] van d'eene plaetse tot d'andere te geraecken

- Interpretation et esclaircissement de certaines dovbtes et difficultez qui se sont recontrées [!] en l'Ordonnance & edict perpetuel [...] du xij. de iuillet de cest an 1611

Now let’s consider the difference between searching for the word English with and without an index.

def split(to_split):

return to_split.split(' ')

def make_word_index(corpus):

index = {}

for title in corpus:

words = split(title)

for word in words:

index.setdefault(word, [])

index[word].append(title)

return index

def search_with_index(search_string, index):

return index[search_string]

def search_without_index(search_string, list_to_search):

result = []

for title in list_to_search:

words = split(title)

if search_string in words:

result.append(title)

return result

result_no_index = search_without_index("English", BOOK_TITLES)

BOOK_TITLES_INDEX = make_word_index(BOOK_TITLES)

result_index = search_with_index("English", BOOK_TITLES_INDEX)

for item in result_index:

print("-", item)

print(result_no_index == result_index)

- English books to be sold by auction Catalogue d'une tres-belle collection de livres en tous genres et langages [...] dont la vente se fera en argent de change, jeudi 18 Frimaire an 11, 9 decembre 1802, et jours suivans, chez Jacques Laureys au Marché aux herbes à Malines

- A new pocket dictionary and vocabulary of the Flemish, English and French languages

- A daily exercise, and devotions, for the young ladies, and gentlewomen pensioners at the monastery of the English canonesses regulars of the holy order of S. Augustin at Bruges

- A brieff apologie, or defence of the catholike ecclesiastical hierarchie, & subordination in England, erected these later yeares by our holy father pope Clement the eyght; and impugned by certayne libels printed & published of late both in Latyn & English

- An appendix to the Apologie, lately set forth, for defence of the hierarchie, and subordination of the English catholike church, impugned by certaine discontented priestes

- A relation of the solemnetie wherewith the catholike princes K. Phillip the III. and quene Margaret were receyed in the English colledge of Valladolid the 22. of August. 1600

- A restitvtion of decayed intelligence: in antiquities. Concerning the most noble and renovvmed English nation

- Dottrina del ben morire. English

- Oratio Petri Frarini quod male reformandae religionis nomine arma sumpserunt sectarii nostri temporis habita. English

True

Obviously, the results of searching with and without a word index are the same. But what about the efficiency of the search? For this we can use Jupyter’s handy feature %timeit:

%timeit search_with_index("English", BOOK_TITLES_INDEX)

%timeit search_without_index("English", BOOK_TITLES)

127 ns ± 7.83 ns per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 10000000 loops each)

49.9 ms ± 3.59 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 10 loops each)

The difference is as large as milliseconds versus nanoseconds (1 ms = 1.000.000 ns)! Remember, with STCV we are only searching about 26,000 titles, but imagine searching a collection like the Library of Congress, which holds over 170 million items…

Time complexity¶

In essence and, what we have just done boils down to changing the time complexity of our search algorithm, i.e. the amount of computer time it takes to run the algorithm.

Time complexity is commonly estimated by counting the number of elementary operations performed by the algorithm, supposing that each elementary operation takes a fixed amount of time to perform. Thus we say that looking for an item in a Python list with length n has a time complexity of O(n), i.e. it could maximally take all n units of time to find it (O stands for “order of”). Accessing a key in a Python dictionary, on the other hand, has a time complexity of O(1), i.e. it always takes just one unit of time.

Optimizing searches by reducing the time complexity of one’s search operation lies at the very heart of searching and is a key aspect to Information Science in particular and Computer Science in general.

(For a good introduction to different time-complexities, read this Medium article).

Complex searches¶

Of course, our example was only a simple one where we built an index that allowed to connect a word with a title. Real-world applications will often build several indices, cross-indices, include variant forms and allow for all kinds of complex searches such as searching with Boolean operators, proximity search, etcetera.

For instance, titles like “The Art of Computer Programming” and “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintanance” could be turned into an AND-index like so:

import json

TITLES = ["The Art of Computer Programming", "Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintanance"]

index = {}

words = []

for title in TITLES:

clean_title = title.casefold()

words = clean_title.split(' ')

for word in words:

index.setdefault(word, {})

for next_word in words:

if next_word == word:

continue

if next_word not in index[word]:

index[word][next_word] = [title]

else:

index[word][next_word].append(title)

# example

print(json.dumps(index["art"], indent=4))

{

"the": [

"The Art of Computer Programming",

"Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintanance"

],

"of": [

"The Art of Computer Programming",

"Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintanance"

],

"computer": [

"The Art of Computer Programming"

],

"programming": [

"The Art of Computer Programming"

],

"zen": [

"Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintanance"

],

"and": [

"Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintanance"

],

"motorcycle": [

"Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintanance"

],

"maintanance": [

"Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintanance"

]

}

In this way, searching with AND becomes easy in this index, e.g. books that combine “art” and “computer”:

print((index.get("art")).get("computer"))

print((index.get("art")).get("motorcycle"))

print((index.get("the")).get("art"))

print((index.get("zen")).get("computer"))

['The Art of Computer Programming']

['Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintanance']

['The Art of Computer Programming', 'Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintanance']

None

Bitmap indexing¶

A lot more can be said about indexing. For one, you might wonder if indexing in itself might not lead to building overly large data structures that take up a lot of space and memory. As was clear from the above example of a combined index, indexing can quickly escalate.

One interesting technique to avoid such problems is bitmap indexing. Wikipedia:Bitmap says:

In computing, a bitmap is a mapping from some domain (for example, a range of integers) to bits

Let’s say you run a pen factory and have produced 10,000,000 pens of a certain type. Now you want to keep track of which pens have been sold by recording their serial numbers. For instance, serial numbers 1, 5 and 10.

from sys import getsizeof

pens_sold = [1, 5, 10]

size = getsizeof(pens_sold)

print(size, 'bytes')

80 bytes

So you need 80 bytes to store this information as a Python array. By the time all pens have been sold the list will be this large:

all_pens_sold = [i for i in range(1,10000000)]

# 1 byte = 0.00000095367432 megabytes

size = getsizeof(all_pens_sold) * 0.00000095367432

print(size, 'megabytes')

77.75120573732737 megabytes

So you see, things can get out of hand quickly. But what if instead of recording all of the serial numbers, you could make a kind of map of serial numbers with the values 1 for sold and 0 for not sold? This is called a bitmap index and if you use a bitmapping system, the overhead is radically different:

# Setting a bit array here with array (https://docs.python.org/3/library/array.html)

# in real applications you should use https://pypi.org/project/bitmap/

import array

# a bit array with bits 1, 5 and 10 set to 1 (= pens sold)

pens_sold = array.array('B', [0b1, 0b0, 0b0, 0b0, 0b1, 0b0, 0b0, 0b0, 0b0, 0b1])

size = getsizeof(pens_sold)

print(size, 'bytes')

# a bit array of ten million sold pens

bitmap_of_all_pens_sold = array.array('B', [0b1 for i in range(1,10000000)])

size = getsizeof(bitmap_of_all_pens_sold) * 0.00000095367432

print(size, 'megabytes')

74 bytes

9.536803281482161 megabytes

Indexing software¶

Lucene¶

The leading software for indexing and searching text is definitely Lucene. However, Lucene is a Java library, which is not easy to implement (especially crossplatform as would be the case in this course).

There is a Python extension for accessing Java Lucene, called PyLucene. Its goal is to allow you to use Lucene’s text indexing and searching capabilities from Python. Still, PyLucene is not a Lucene port but a Python wrapper around Java Lucene. PyLucene embeds a Java VM with Lucene into a Python process. This means that you still need Java Lucene to run PyLucene, and some additional tools (GNU Make, a C++ compiler, …).

Whoosh¶

As text indexing/searching is bound to be really slow in Python (so it make good sense to stick to Java Lucene) there is no true pure-Python alternative to Lucene. However, there are some libraries that allow you to experiment with similar indexing/searching software. (Also check out this interesting tutorial for building a Python full-text search engine!)

One of these is Whoosh, which is unfortunately no longer maintained. Still, the most recent version, 2.7.4, is quite stable and still works fine for Python 3. It can easily be installed through pip install Whoosh.

In the Whoosh introduction we read:

About Whoosh

Whoosh is fast, but uses only pure Python, so it will run anywhere Python runs, without requiring a compiler.

Whoosh creates fairly small indexes compared to many other search libraries.

All indexed text in Whoosh must be unicode.

What is Woosh

Whoosh is a fast, pure Python search engine library.

The primary design impetus of Whoosh is that it is pure Python. You should be able to use Whoosh anywhere you can use Python, no compiler or Java required.

Like one of its ancestors, Lucene, Whoosh is not really a search engine, it’s a programmer library for creating a search engine.

Practically no important behavior of Whoosh is hard-coded. Indexing of text, the level of information stored for each term in each field, parsing of search queries, the types of queries allowed, scoring algorithms, etc. are all customizable, replaceable, and extensible.

Indeed, Whoosh is quite similar to Lucene, including its query language. It lets you connect terms with AND or OR, eliminate terms with NOT, group terms together into clauses with parentheses, do range, prefix, and wilcard queries, and specify different fields to search.

The following code shows you how to create and search a basic Whoosh index. For more information, see the Whoosh quick start and documentation on the query language.

"""

Whoosh quick start

https://whoosh.readthedocs.io/en/latest/quickstart.html

"""

import os

from whoosh import highlight

from whoosh.index import create_in

from whoosh.fields import Schema, ID, TEXT

from whoosh.qparser import QueryParser

CORPUS = "corpus_of_british_fiction"

# Create schema

"""

To begin using Whoosh, you need an index object. The first time you create

an index, you must define the index's schema. The schema lists the fields in

the index. A field is a piece of information for each document in the index,

such as its title or text content. A field can be indexed (meaning it can be

searched) and/or stored (meaning the value that gets indexed is returned with

the results; this is useful for fields such as the title).

"""

schema = Schema(title=TEXT(stored=True),

content=TEXT(stored=True),

path=ID(stored=True))

# Create index

"""

Once you have the schema, you can create an Index object.

At a low level, this creates a Storage object to contain the index.

A Storage object represents that medium in which the index will be stored.

Usually this will be FileStorage, which stores the index as a set of files

in a directory. Hence, you will need a directory.

"""

if not os.path.exists("index"):

os.mkdir("index")

my_index = create_in("index", schema)

# Add documents

"""

Once we've got an Index object, we can start adding documents.

The writer() method of the Index object returns an IndexWriter object that

lets you add documents to the index. The IndexWriter's .add_document()

method accepts keyword arguments where the field name is mapped to a value.

Once you have finished with the writer, you need to commit it.

The documents we add, a small corpus of British fiction, are part of

the course repo.

"""

writer = my_index.writer()

# Corpus courtesy of Maciej Eder (http://maciejeder.org/)

for document in os.listdir(CORPUS):

if document.endswith(".txt"):

filepath = os.path.join(CORPUS, document)

with open(filepath, 'r') as text:

writer.add_document(title=document,

content=str(text.read()),

path=document)

writer.commit()

# Parse a query string

"""

Woosh's Searcher (cf. infra) takes a Query object. You can construct query

objects directly or use a query parser to parse a query string.

To parse a query string, you can use the default query parser in the qparser

module. The first argument in the QueryParser constructor is the default field

to search. This is usually the "body text" field. The second (optional) argument

is a schema to use to understand how to parse the fields. The argument of

the .parse() method is a query in Whoosh query language (similar to Lucene):

https://whoosh.readthedocs.io/en/latest/querylang.html

"""

myquery = QueryParser("content", my_index.schema).parse('smattering')

# compare results for:

# myquery = QueryParser("content", my_index.schema).parse('smattering in surgery')

# myquery = QueryParser("content", my_index.schema).parse('smattering NOT surgery')

# Search documents

"""

Once you have a Searcher and a query object, you can use the Searcher's

.search() method to run the query and get a Results object.

You can use the highlights() method on the whoosh.searching.Hit object

to get highlighted snippets from the document containing the search terms.

To limit the text displayed, you use a Fragmenter. More information at:

https://whoosh.readthedocs.io/en/latest/searching.html

"""

with my_index.searcher() as searcher:

# Search

# limit=None -> search all documents in index

results = searcher.search(myquery, limit=None)

print(results)

# Print paths that match

for hit in results:

print(hit["path"])

<Top 2 Results for Term('content', 'smattering') runtime=0.0007309279990295181>

Thackeray_Barry.txt

Fielding_Joseph.txt

with my_index.searcher() as searcher:

results = searcher.search(myquery, limit=None)

# Print examples of matching text with highlights and fragmenter

# Use (default) context fragmenter

# https://whoosh.readthedocs.io/en/latest/highlight.html#the-character-limit

results.fragmenter = highlight.ContextFragmenter(charlimit=None)

for index, hit in enumerate(results):

print(index+1, hit["path"], "=", hit.highlights("content"))

1 Thackeray_Barry.txt = that he had no <b class="match term0">smattering</b> of

chemistry...of tune. She had a <b class="match term0">smattering</b> of half-

a-dozen...to me;

for I had a <b class="match term0">smattering</b> of French--and

2 Fielding_Joseph.txt = I have

a small <b class="match term0">smattering</b> in surgery," answered...the gentleman.--"A

<b class="match term0">smattering</b>--ho, ho, ho!" said...I believe it is a

<b class="match term0">smattering</b> indeed."

The company

Exercise: Morphology tool¶

Use Whoosh to illustrate English morphology with examples from a given corpus. For instance, the rules of morphology dictate verbs can take different forms or be used to form nouns, adjectives and such, like:

render: ‘renders’, ‘rendered’, ‘rendering’think: ‘thinks’, ‘thought’, ‘thinking’, ‘thinker’, ‘thinkers’, ‘thinkable’put: ‘puts’, ‘putting’, ‘putter’do: ‘does’, ‘did’, ‘done’, ‘doing’, ‘doings’, ‘doer’, ‘doers’

Forms like think, put and do illustrate that you cannot approach this problem in a mechanical or brute-force way. It is not as simple as adding ‘ed’, ‘ing’, etcetera to the verbs. Sometimes consonants are doubled, sometimes the verb stem changes (in the case of strong verbs), and so on.

Whoosh has a particular feature to deal with this. Look through the documentation and you’ll find it easily.

Use it to build a Python application that takes a word as input and returns a list of sentences from the British fiction corpus that contain this word to illustrate its usage. Think about building the index first, so you can then reuse it (without having to rebuild it) for additional searches.

Also, try to display the results nicely, i.e. without the markup tags and whitespace (line breaks, etc.) we saw in the above example. Maybe you can even print the matched word in bold?